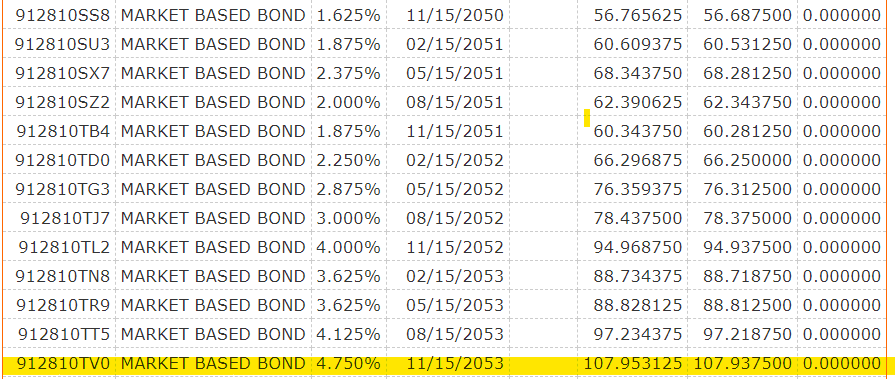

The dominant theme in financial markets in the fourth quarter of 2023 was the huge rally in US Treasuries following indications from the Fed it will likely cut rates in 2024. The bond we wrote about in our November 15 piece "Failed Treasury Auction?" has rallied by +8pts since its primary issuance at 99.70, closing yesterday at around 108:

61% IRR; not bad for a fixed income investment.

The rapid repricing of Treasuries along the curve coincided with a risk-on rally to finish off 2023. The price action at times felt like "panic buying," likely the result of a combination short-covering, investors making up for being under-indexed stocks throughout the year, and an anticipation of Fed rate cuts in 2024.

The last point here is important: as market participants anticipate the Fed will cut rates in 2024, the yields on Treasury securities come down (which means prices go up). Investors generally have a return target they aim to hit, so as treasuries yield less, higher-yielding corporate bonds and stocks become relatively more attractive. Market participants understand all of these factors, and the breakneck-rally we experienced can be thought of as investors "front-running" the Fed's expected rate cuts and subsequent rotation out of Treasuries and into corporate credits and equities. Of course, the fiscal spending surge played its usual role in supplying the firepower necessary to propel stocks upward.

In our view, there is a risk that the market is over-weighting the Fed's expected rate cuts in 2024. Our rationale is that rate hikes mechanically support inflation. Isabella Weber, a rising star in the heterodox economics world, has a very articulate explanation for what she has termed "seller's inflation:"

"(1) Rising prices in systemically significant upstream sectors due to commodity market dynamics or bottlenecks create windfall profits and provide an impulse for further price hikes. (2) To protect profit margins from rising costs, downstream sectors propagate, or in cases of temporary monopolies due to bottlenecks, amplify price pressures. (3) Labor responds by trying to fend off real wage declines in the conflict stage. We argue that such sellers’ inflation generates a general price rise which may be transitory, but can also lead to self-sustaining inflationary spirals under certain conditions."

We would add to Ms. Weber's point here that higher interest rates should be included in the "rising prices in systematically significant upstream sectors" she refers to. A higher cost of funds is a real expense that affects a company's P&L and, therefore, its pricing strategy. Given higher costs, companies must raise prices to maintain their margins. So monopolistic price-takers can be expected to raise prices in a rising-rate environment, and the interest that the government pays on its debt (and Fed pays on reserves) supplies the income necessary to support these higher prices.

Another way to think about the impact of rate hikes on prices is to consider what Warren Mosler has dubbed the "term structure of prices." From his MMT white paper:

"Furthermore, forward pricing is a direct function of the Fed’s policy rate, and with a policy of a positive term structure of interest rates, the forward price level increases continuously at the policy rate, which is the academic definition of inflation."

Indeed, higher interest rates can be thought of as inflation by government decree. The forward rates curve is a function of market expectations for where the Fed will set its policy rate in the future, and is a real cost of doing business. If a producer of hot-rolled coil steel has an option of selling in the spot market at $1,000/ton today vs. the 1-year forward market, and the 1-year risk-free-rate is 5%, all things equal it will raise its price by 5% (i.e. $1,050/ton) to reflect the opportunity cost of selling today, pocketing the cash, and earning 5% of free interest in a year. Thus, by allowing the market to set rates at 5%, the government is essentially reducing the nominal purchasing power of its money by 5% per year, which is equivalent to saying the price to purchase real goods and services in a year is 5% higher.

Anecdotally, we have witnessed signs of local monopolistic firms raising prices at around the Fed's policy rate. For example, in CT (where Ryan lives) Connecticut Natural Gas recently announced a 4% rate increase, its first since 2018. Similarly, Metro-North, the commuter rail to NYC, announced a 4.5% increase in ticket fares, also the first since 2018. Of course, 2018 was the last time prior to 2022 that the Fed had raised rates.

In the post-GFC ZIRP period, US inflation (as defined by CPI) consistently failed to reach the Fed's 2% target. Japan, which has had interest rates near 0% for nearly a quarter century, has had the lowest inflation in the developed world. Since the Fed began hiking rates in 2022, inflation has been said to be frustratingly "sticky." And last Thursday, preliminary reports showed CPI came in a bit higher than most expected. Coincidence? We think not. The evidence is overwhelming that rate hikes lead to higher inflation, and vice versa. In other words, the Fed has it backwards.

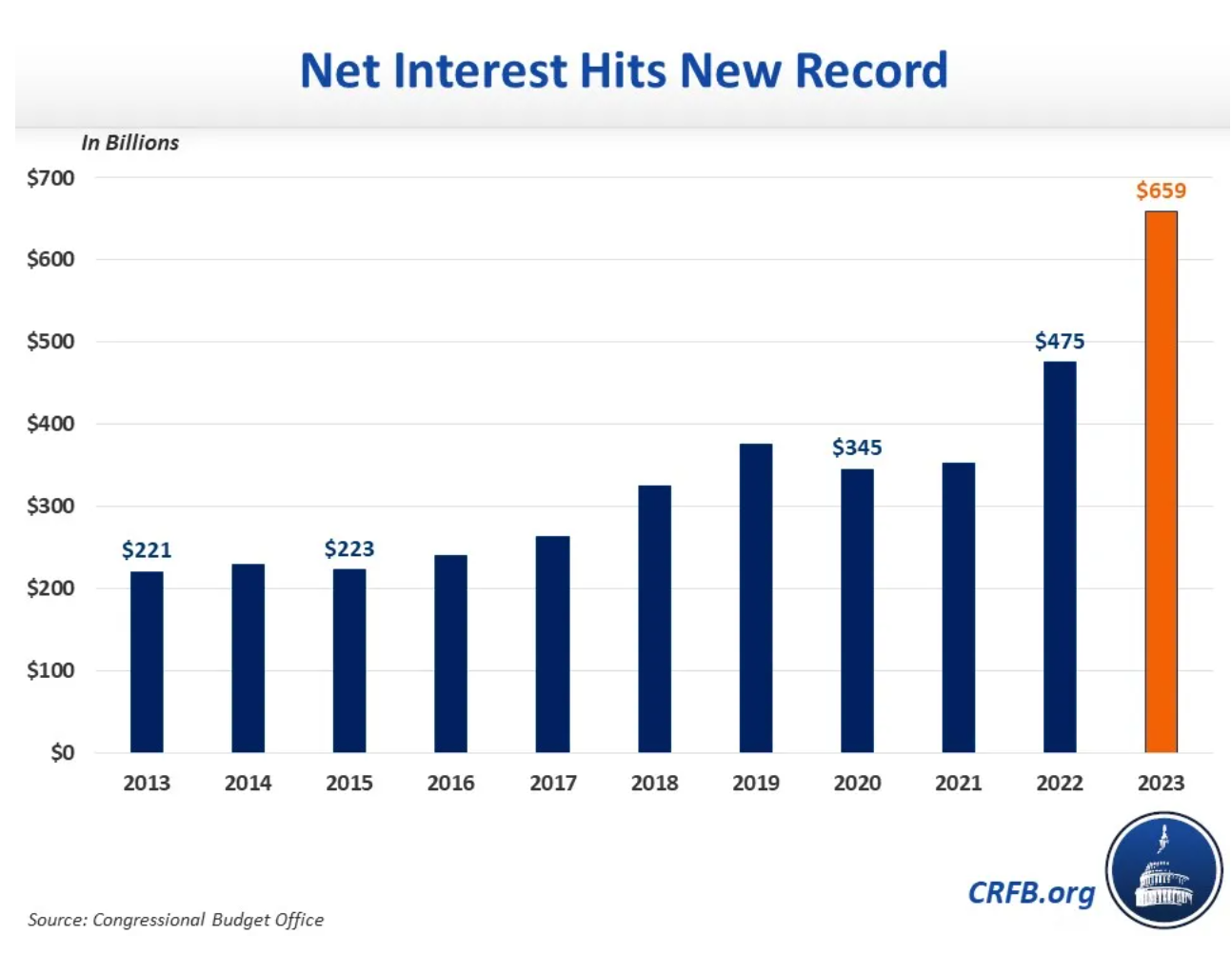

By mistaking water for gasoline to fight the inflation fire, the Fed is creating a risk of runaway inflation. With US federal debt to GDP at around 120%, the Fed's rate hikes are adding substantial fiscal stimulus to the US economy to the tune of $659 billion in fiscal year 2023:

Recall that net interest paid by the US government represents income for US households, businesses, municipalities, and foreign countries. This income adds reserves to banks' balance sheets which creates demand for more Treasury securities, which earn interest at a similar rate, further adding income to the non-government sector and potentially accelerating a cycle of higher and higher inflation. This can lead to a reinforcing cycle where higher rates beget higher prices, which the Fed responds to by further hiking rates. With futures markets pricing in six rate cuts in 2024, we'll take the under.

Taking all this into consideration, where are some attractive places to park one's savings in 2024? Below are a few ideas:

1. Low-Duration High-Yield Credit: If the Fed keeps rates flat or doesn't cut very much, the extra stimulus will support household spending, corporate profits, capital spending and employment. This type of scenario generally leads to low corporate default rates. And staying in bonds near their maturity reduces duration risk should we experience a "bear steepener" yield curve move.

2. Banks: Banks stocks underperformed in 2023 relative to other sectors following the second (First Republic) and third (Silicon Valley Bank) largest bank failures in US history. Many such equities today trade for single-digit P/E multiples. Buying bank stocks gives investors exposure to credit assets in an environment with economic growth expected to continue to be strong. And there tends to be a lag effect between rising funding costs and yields on interest-earning assets, which we expect to be a tailwind for reported earnings in 2024. The Fed last hiked rates in July 2023, so we can expect deposit costs to stay flattish while older, lower-yielding loans and securities mature and are replaced with new higher-yielding paper. Just be sure avoid those with heavy exposure to potential credit losses in their commercial real estate portfolio, as office vacancy rates are currently at record highs.

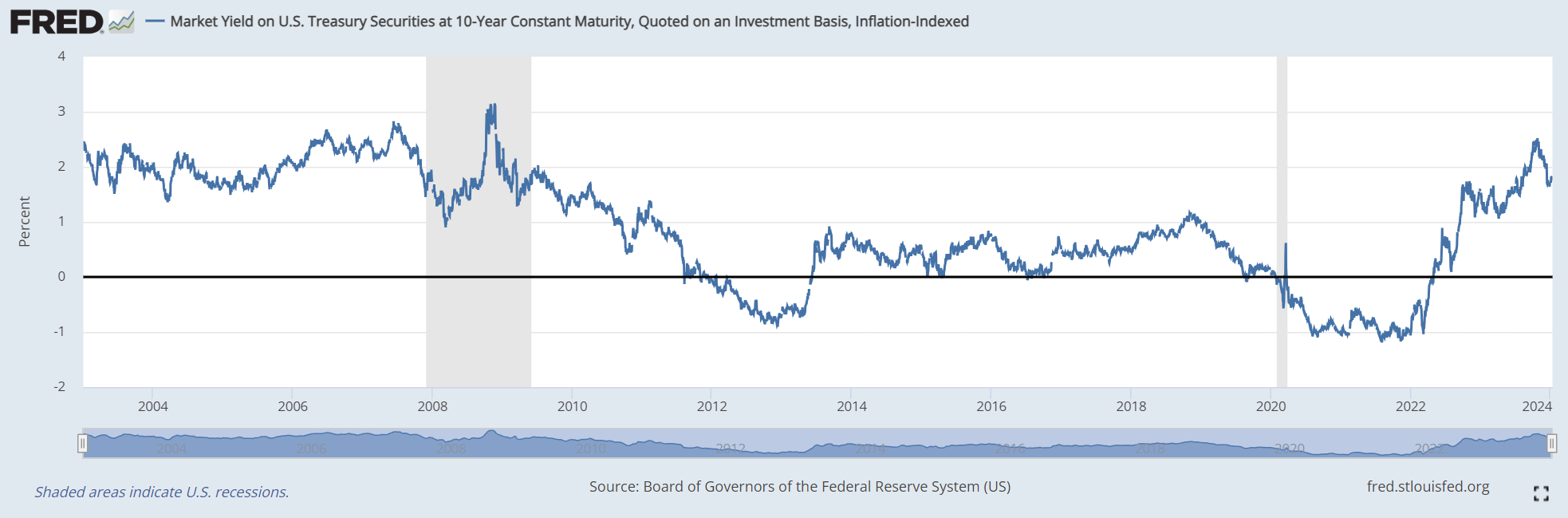

3. TIPS: While market yields on US Treasury Inflation Protected Securities have come down since the fall, they are still around a 15-year high, and offer investors protection should inflation start rising again:

While we are certainly not alone in the investment world who believe there is a real risk of rates and inflation remaining stickier than most expect, we would argue our reasoning differs from most if not all others.

The biggest wildcard for 2024 is energy. We have maintained a bearish view on oil prices since April 2023 when the Saudis announced production cuts, which signaled weak demand for crude. Meanwhile, US oil production reached an all-time high in 2023. We view this as functionally a tax cut for the American consumer, and believe this has contributed to the strong economic growth. And the Saudis recently announced further OSP cuts, a sign that the market remains oversupplied. Given that CPI is heavily influenced by oil prices, persistent weakness in the price of crude can help offset the Fed's inflationary rate-hikes, and if inflation is low enough, it may induce the Fed to cut. This presents the biggest challenge to our "higher for longer" thesis.

Of course, geopolitical risks and/or a recovery in Chinese demand for crude may enable the Saudis to start raising prices again. Investors may want to consider adding their exposure to the energy sector as a hedge.

Wishing everyone all the best in 2024!