Wall Street Titans Issue Mea Culpa

Wall Street titans Jamie Dimon and Ray Dalio openly admit to misjudging the economy's direction, with their predicted crises not materializing. This piece explores their reflections on these errors and the enduring strength of the economy, highlighting lessons in humility and foresight.

Earlier this month, the Wall Street Journal published the following piece: "Jamie Dimon and Ray Dalio Warned of an Economic Disaster That Never Came. What Now?" In it, both Dimon and Dalio issued mea culpas following 2022 predictions of economic calamity that never materialized. As mentioned in the article, Dimon warned of a coming economic "hurricane" and Dalio predicted a "debt crisis."

Of course, neither came to pass. The March 2023 regional banking crisis amounted to idiosyncratic, rather than systemic, problems at specific rogue banks that had less-sticky deposits than they thought (see: Silicon Valley Bank $SVB and First Republic Bank $FRC) or were crypto banks engaged in money laundering operations (see: Silvergate Capital $SI and Signature Bank $SBNY). The failures of these institutions had minimal impact on the economy, and Mr. Dimon ended up with a shiny new toy by acquiring First Republic out of receivership from the FDIC.

And it wasn't just Dalio and Dimon; the article mentions other high-profile Wall Street titans including Jeffrey Gundlach (who predicted a recession would hit "in a few months" about a year ago) and David Rosenberg.

The following passage is instructive (emphasis added):

The experts were way off. They underestimated the impact of government stimulus and the resilience of consumers and businesses. And they were too skeptical of the Federal Reserve’s ability to push inflation lower without sparking a recession. The economy continues to grow at a steady clip. Inflation is getting closer to the Fed’s goal of 2%, unemployment remains near a half-century low and the stock market is near record highs.

To their credit, both Dalio and Dimon appear to humbly acknowledge their mistakes. Each of them explains their rationale for why they got it wrong, which offers a glimpse into how both men think about how the economy and financial system operate. Here is Mr. Dalio (emphasis added):

I was bearish on the economy. I got it wrong...I got it wrong because, ordinarily, when you raise interest rates it curtails private-sector demand and asset prices and slows things down, but that didn't happen. There was a historic transfer of wealth: the balance sheets of the private sector improved a lot and the balance sheet of the government deteriorated a lot.

The point on interest rates is exactly backwards. As a reminder, a dollar borrowed is a dollar saved: someone's debt liability is someone else's credit asset. What's expensive for borrowers is cheap for lenders by definition. And on balance, the U.S. federal government is a net payer of interest to the private sector. So when the Fed raises rates, the impact is two-fold: 1) it shifts the distribution of real output from debtors to creditors and 2) assuming there is some slack in the economy, it results in higher aggregate output as recipients of interest paid on government liabilities spend that additional income. At the end of the day, raising interest rates means savers have more dollars available to spend at the end of the year than they did at the beginning, all else being equal. Anyone with a basic interest-paying checking account at a bank intuitively understands this.

Further, saying private sector balance sheets improved while government balance sheets "deteriorated" is both redundant and misleading. As Stephanie Kelton likes to put it, "their red ink is our black ink:"

Please remember that every “scary” headline that 🚨 the GOVERNMENT DEFICIT is just reporting the corresponding financial SURPLUS that appears on the NON-GOVERNMENT ledger. Their red ink makes our black ink possible. https://t.co/4t113lElE0 pic.twitter.com/M6tYsk16oJ

— Stephanie Kelton (@StephanieKelton) June 12, 2023

This is not an opinion; it is an incontrovertible truth. There is no other way for the U.S. private sector to have a surplus in USD financial assets other than for the federal government to issue those assets in the first place. Our standard practice is to utilize double-entry bookkeeping to record the creations of both private sector financial assets and government liabilities. The latter does not constitute any sort of deterioration; it is a Standard Operating Procedure – or, as we like to call it: accounting.

In a way, we feel vindicated by these comments. Mr. Dalio sees the same data we see, but lacks the correct framework to be able to accurately predict the downstream impacts of the Fed's rate hikes.

I would have thought some of the fiscal stimulus would have worn off by now. - Jamie Dimon

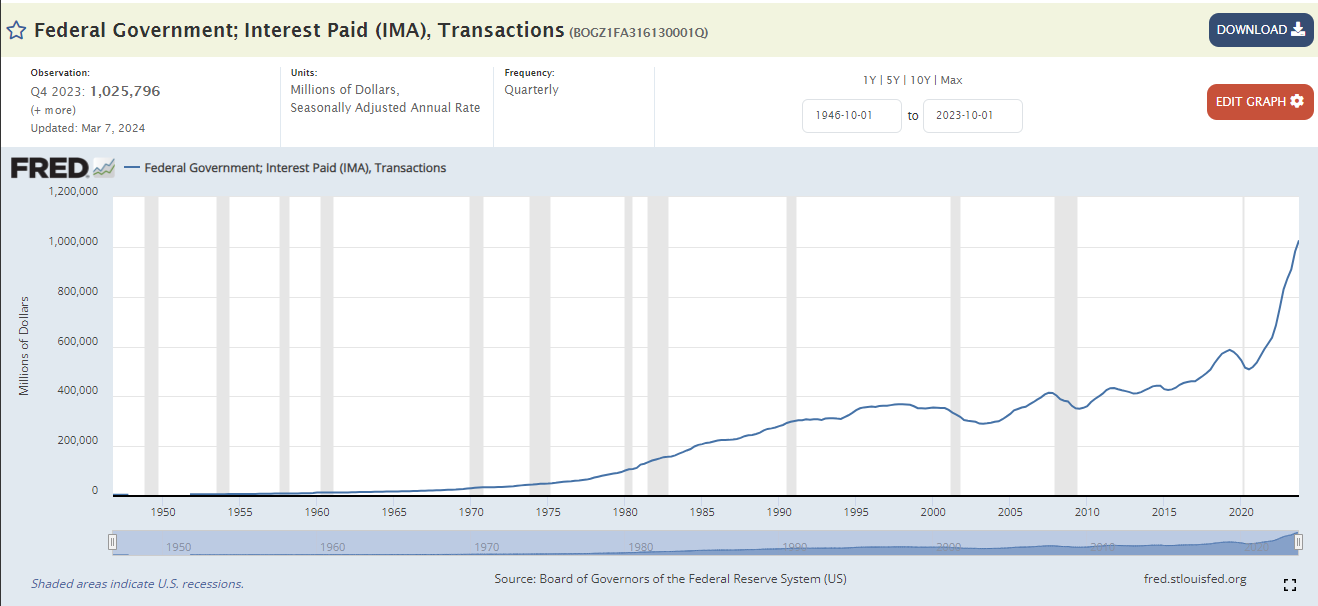

This is a puzzling admission from Mr. Dimon. It seems like he is referring to the 2020/2021 pandemic-inspired stimulus programs. According to the NBER, 58% of the stimulus payments were kept as savings or used to pay down debt. The private sector de-leveraging that took place was substantial, and created balance sheet capacity for continued spending. In addition, several new government spending programs were announced in 2022, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the CHIPS and Science Act. And that is before considering the stimulative impact of the Fed's rate hikes, for which the current run-rate is over $1 trillion:

It's unclear why he would expect the stimulus to "wear off" given these policies. As CEO of the largest bank by market capitalization in the U.S., Mr. Dimon has access to incredible amounts of exclusive, real-time data and resources with which to make predictions. JPMorgan has armies of researchers, analysts, economists, and bankers, and yet it can't get basic and obvious predictions right because it lacks the correct framing.

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that Dimon attributes the recovery to federal government "stimulus," as it affirms our view that increases in U.S. federal spending (which includes interest paid on its liabilities) has supported and is continuing to support the economy in aggregate. With fiscal deficits remaining high, we can expect the expansion to continue.

Dalio and Dimon's (along with the rest of Wall Street) failed predictions were not the result of a lack of access to data and information. Indeed, they are two of the most well-informed financial persons on the planet. They got it wrong because of a flawed framework with which to apply the relevant data.

The late Charlie Munger (RIP) spoke of the virtues of using "mental models" to enhance decision-making in investments and business. Sometimes, having a better framework/mental model trumps having more data. At AppliedMMT, we use a simple observation, that modern money is a public monopoly, to create mental as well as mathematical models which we believe more correctly reflect the reality of how monetary systems function. By doing so, we believe we can avoid many of the mistakes that Wall Street tends to make.